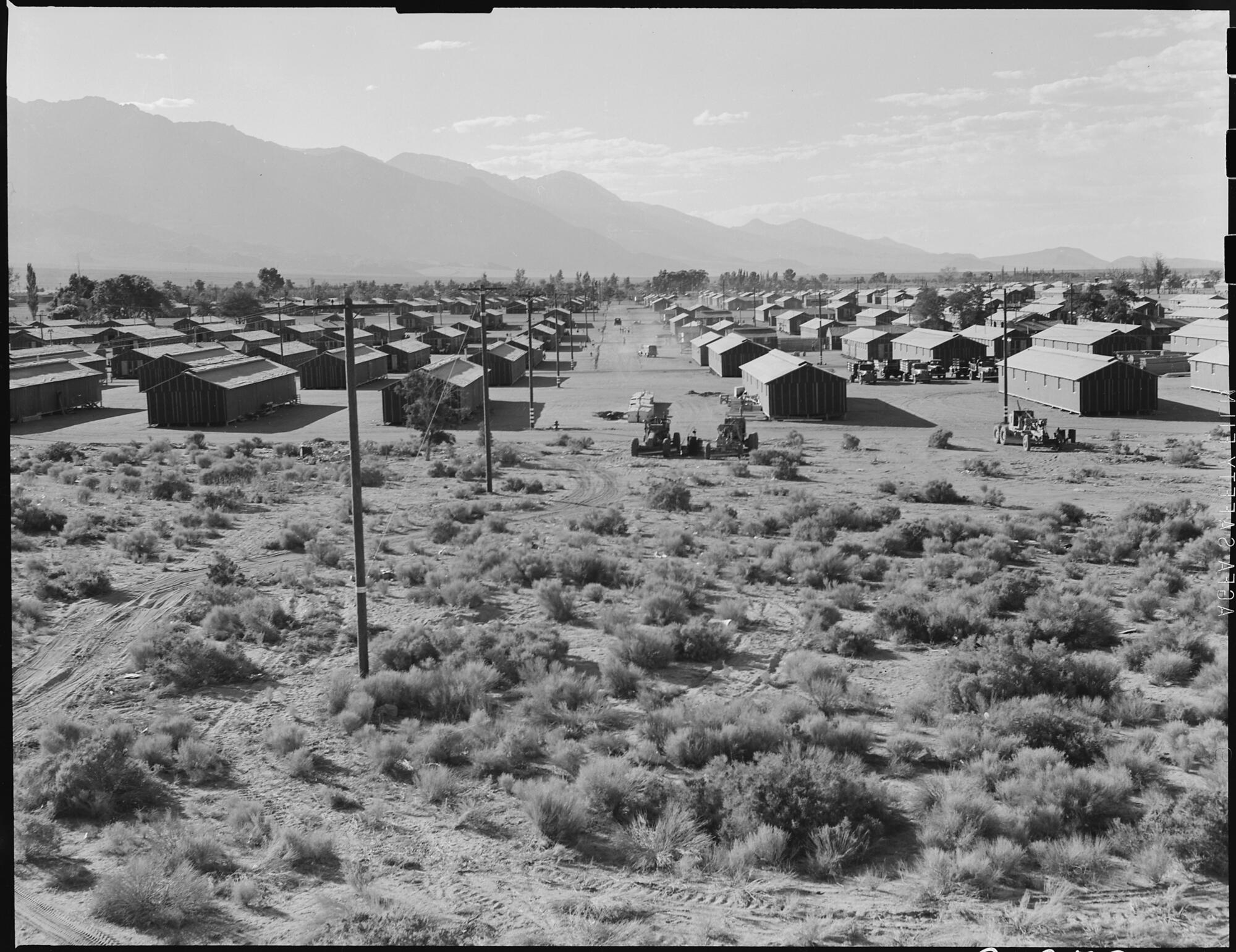

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, allowing the military to forcibly relocate over 120,000 Japanese-Americans to internment camps in the US desert. While most were US citizens, men, women, and children were imprisoned without trial—or even being accused of a crime—for three and a half years.

It took Congress over 40 years to admit this a “grave injustice” and issue an apology, saying in part that: “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership” had eclipsed the United States Constitution.

Buddhists—the majority of the Japanese-American community—were particularly singled out in this period of internment. Without evidence, the FBI and the War Relocation Authority claimed Buddhists were more likely to support Japan than their own country. Priests were especially targeted, as they were thought to be even more unable to assimilate into American society than the average Buddhist. The FBI classified Buddhist priests as “known dangerous Group A suspects,” and rounded them up first. In fact, as rumors spread among Japanese- Americans that Buddhists were being treated more harshly than Christians, some Buddhists converted to Christianity.

Buddhists responded to their internment in a variety of ways. For many, Buddhism provided a refuge from the struggle that they were forced to suffer during the war. Before their internment, Japanese-Americans were given between a week and ten days to sell or store all their belongings; they were only allowed to bring to the camps what they could carry. Faced with this frightening reality, many Buddhist temples opened their doors to the local Japanese-American population as storage spaces for their belongings. Once in the camp, many American Buddhists found that Buddhist teachings on suffering helped them to understand and alleviate the betrayal and confusion that they felt after being imprisoned by their own government. Buddhists in the camp maintained family and community ties through religious rituals which honored their ancestors, performing marriages and funerals, and erecting a monument to the honor the dead (see right). Some Buddhists, who had family fighting for the United States in Europe expressed confidence that the Buddha would serve as a protector for their loved ones.

Still, while American Buddhists found refuge and resistance in their tradition, the period was also a time of significant changes in American Buddhism, as oppressed Japanese-American Buddhists worked to profess their loyalty to the United States and end their captivity. Many Buddhists attempted to adapt their religious practices to look more “Christian” in order to avoid the ire of the discriminatory authorities. For example, the Buddhist Mission of North America—the largest Buddhist organization in the US—changed its name to the Buddhist Churches of America. Interned Buddhists met on Sundays in “camp churches” and sang from new hymnals which imitated the medium of Christian songbooks. In addition, the swastika—a common symbol in Buddhism which predated the Nazi’s use of a similar symbol by thousands of years—was almost completely removed from the American Buddhist tradition, replaced with the symbol of a dharma wheel. The internal diversity of the Buddhist traditions was also suppressed in the camps, as authorities forced the diverse sects in the camps to perform their religious rituals and services together, regardless of their differences. Through it all, many Buddhists struggled to show the American government that their religion was not incompatible with loyalty to the United States.

Of course, for interned Buddhists, resistance against these oppressive government policies and efforts to assimilate into American society often went hand in hand. The complex ethnic and religious loyalties that Japanese-Americans had to both their home in the United States and their ethnic and religious heritage in Japan caused interned Buddhists to have many and mixed responses to their struggle. The internment of Japanese-Americans during WWII was a dark chapter in American history, deeply shaped by the power of “race prejudice [and] war hysteria." However, it was also deeply shaped by the Buddhist faith.

Additional Resources

Primary Sources:

- Executive Order 9066: http://bit.ly/1W12RXV

- Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (Official US Government Apology): http://bit.ly/1QYe1di

- Photographs of the Manzanar Camp by Dorothea Lange: http://bit.ly/1oChRwZ

Secondary Sources:

- FDR Presidential Library Video on Executive Order 9066: http://bit.ly/2mx1Ibi

- Excerpt from PBS Documentary on Lange and Internment: http://bit.ly/2m6kGdK

Discussion Questions

- How does the response of Buddhists to their internment show how Buddhism is internally diverse?

- How did the historical and cultural context of Japanese-American Buddhists shape the way that they practiced their religion?

- How did the trauma of internment change strands of American Buddhism?

- Why do you think that Japanese-American Buddhists were considered more dangerous than non-Buddhists?

- Look at the series of photos in the primary source above from the famous American photographer Dorothea Lange. What do the photos tell you about the internment camps? About the Japanese-Americans who lived there? What might be missing from these photos? How might the fact that Lange was commissioned by the US government’s War Relocation Authority (WRA) to take these photos change the way you view them? Note that 97% of Lange’s photos for the WRA were never published.